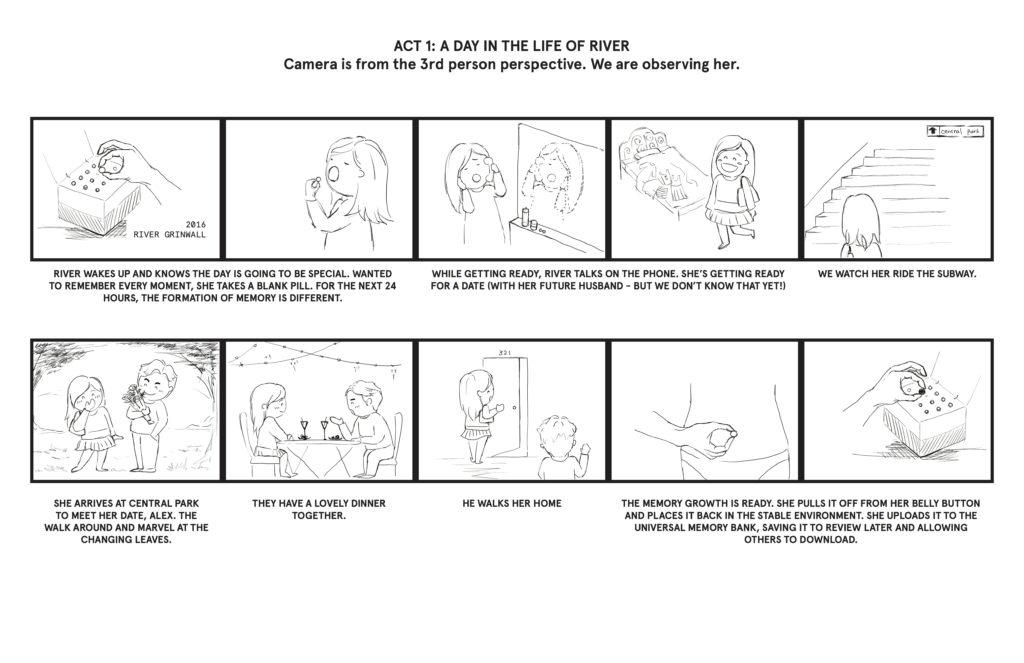

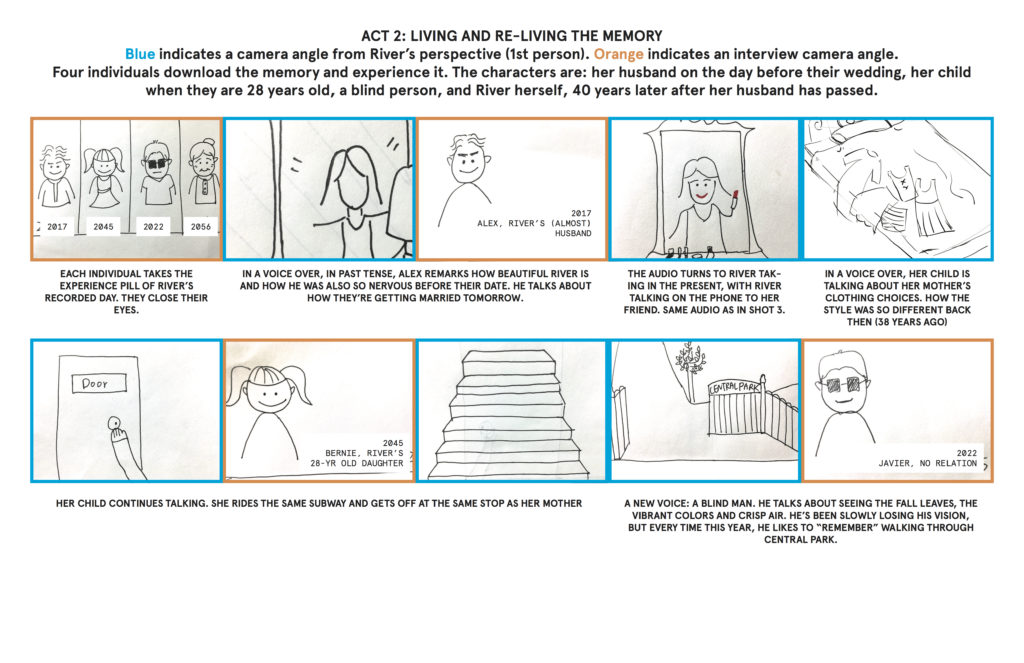

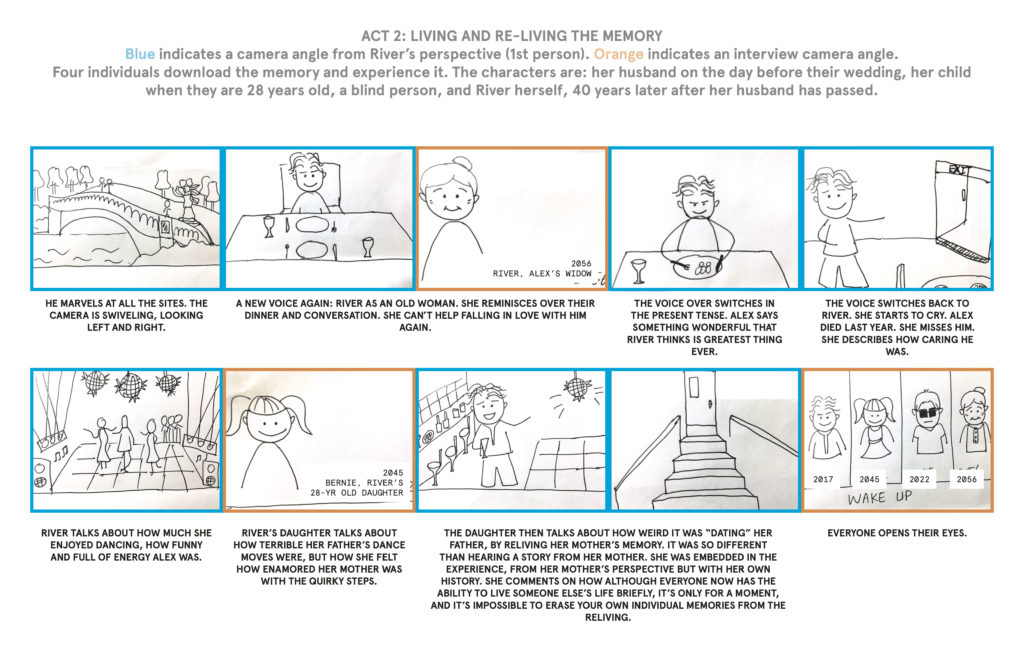

Synchrony occurs when events operate or occur in unison. At the core of synchrony is the passage of time and a change (the event) occurring within this. “Events” refer to a change in something—sound, motion, visuals, etc. Something was on, and then it wasn’t. Something was here, and then it was there. The other component of synchrony the relationship between multiple events; synchrony cannot be identified in isolation. When exploring synchrony, the questions to ask are:

- What are the events, or what things are changing?

- What is the duration of the relationship?

In the physical world around us rarely are events synchronized. We walk at a different pace that those around us, cars accelerate at difference speeds when the light switches from red to green. But this is why our attention can be captured by synchronicity. Since it’s so uncommon, we often take note when objects, people, actions or sounds around us are in sync. Sometimes this synchronicity is planned and part of a performance, such as an orchestra playing to the time kept by a conductor.

Sometimes it happens by chance. There’s a goofy scene in Scrubs in which the sounds playing in JD’s headphones seemingly align with the actions and movements of those around him.

I’m interested in exploring how changes in synchrony and asynchrony may affect the attention of a user or focal point of a piece of work. What interactions can be used to adjust the synchrony of events? Can users only participate in a piece if they perform synchronously? How does synchrony or asynchrony affect their behaviour?

Complete Audio and Visual Synchrony

Jono Brandel created Patatap, a keyboard-controlled sound and visual animation platform. Individual sounds and short animated elements are mapped to each key. Pressing the spacebar produces a new colour scheme as well as a new set of sounds. When keys are played systematically, the user can generate melodies and rhythm. At an event in San Fransisco, Brandel himself demonstrated this with the help of a looper (I think?)

What’s particularly evident in the performance video is how intertwined and inseparable the sounds and visuals are. Each time the colour background swipes across the screen, it reinforces the underlying beat. Perhaps this level of synchronicity is particularly suited for the type of electronic sounds available in the platform. Like each animation, each sound is triggered in isolation and appears/is heard precisely. There is overlap between sounds and visuals but the trigger and their presentation to the audience occurs individually.

Variable Synchrony and Asynchrony

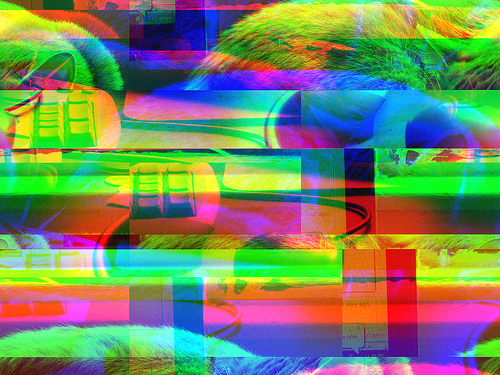

In Bon Iver’s recent music video for 29 #Strafford APTS, the audio is accompanied by distorted visuals that are akin to seeing through a kaleidoscope. The visuals at the beginning of the song seem to take inspiration from Joseph Albers, composed of colour blocks with stark edges. Yet this clarity and precision is disrupted by the effects of the kaleidoscope—they become layered, multiplied and seemingly of a dream state. They transformation of visuals and effect of the kaleidoscope do not seem to be tied to the audio. Changes happen without regularity. The computer generated graphic compositions switch to recorded footage of birds, a bedroom, nature. Yet there is one striking moment of alignment between the music and visuals. After zooming into a psychedelic-like sunburst graphic that was above the bed, and seeing the pixel grain of screen which is showing this digital image, at 2:53 both the music and visual “snap out of it” – almost like waking up out of the dream. With the reappearance of words layered on the visuals, the viewer/listener is reminded that a story is being told. The dream state they were lulled in to through the use of asynchrony and blended changed is disrupted by the sudden alignment of sound and visual.

Work in Progress

To explore this idea of visual and auditory synchronization, I want to create a potentially-interactive animation to be coupled with a previous sound piece I worked on. In early prototyping, I’ve started looking at how to get objects moving independently.

I imagine building out a larger prototype in which multiple objects are synchronized to different aspects of an audio clip. Maybe changes in volume result in something changing size, or an object appears and disappears in line with the beat. Are all objects simultaneously synchronized with the audio or do they each come in and out of sync independently?