One Simple Sentence

Aunt Dan & Lemon is a play about how we individually reckon with the complex moral questions and decisions which form our society.

One Complex Sentence

Obsessions*, in that they rationalize a series of incremental and subtly unconscionable assessments of ourselves and others, can lead to a passive decoupling from morality.

*Obsessions being where we individually derive meaning for our lives: Aunt Dan’s infatuation with Kissinger, Lemon’s undying devotion to and adoration of Aunt Dan but also juice thing(?), Mindy’s thirst for money, the father’s fixation with work. Sidenote: I’m not convinced of my use of ‘obsession’ but I haven’t yet found a more precise term yet.

Three to Five Sentence Description

Through a series of fragmented flashbacks, Lemon illustrates how her detached and morally indifferent worldview has been shaped by Aunt Dan, a former friend of her mother’s. During a formative summer when Lemon was eleven years old, Aunt Dan captivated her with stories of self-indulgent friends and an irrational obsession with Kissinger. Now frail and isolated, Lemon remains firmly planted in the views offered by her Aunt Dan but extends them further. She expresses a sympathy and adoration towards the Nazis and justifies their mass murders as a simple human behavior meant to preserve their way of life.

Fusch’s Reading

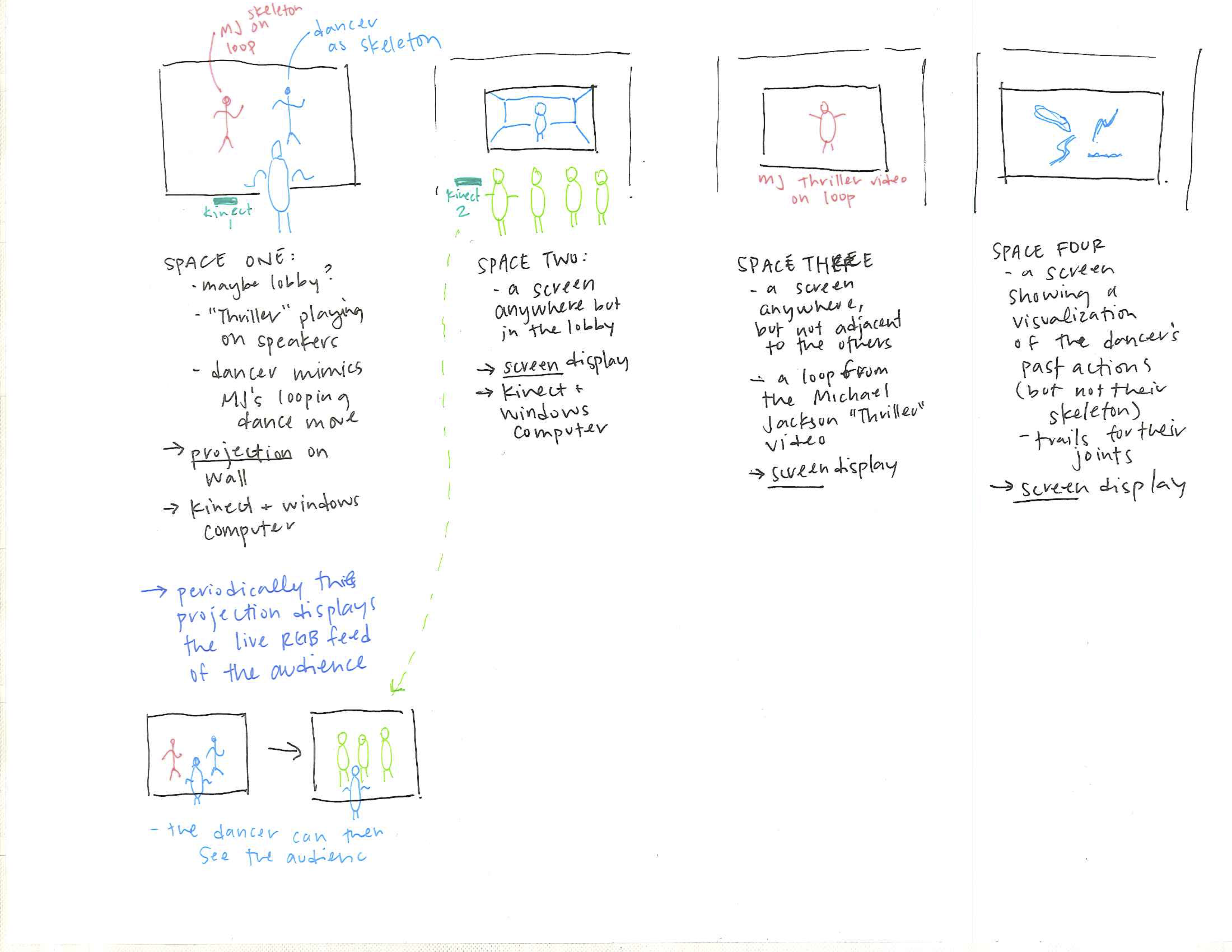

Key spaces: the bedroom in the house in the garden, the garden itself

Key times: present day Lemon, childhood Lemon

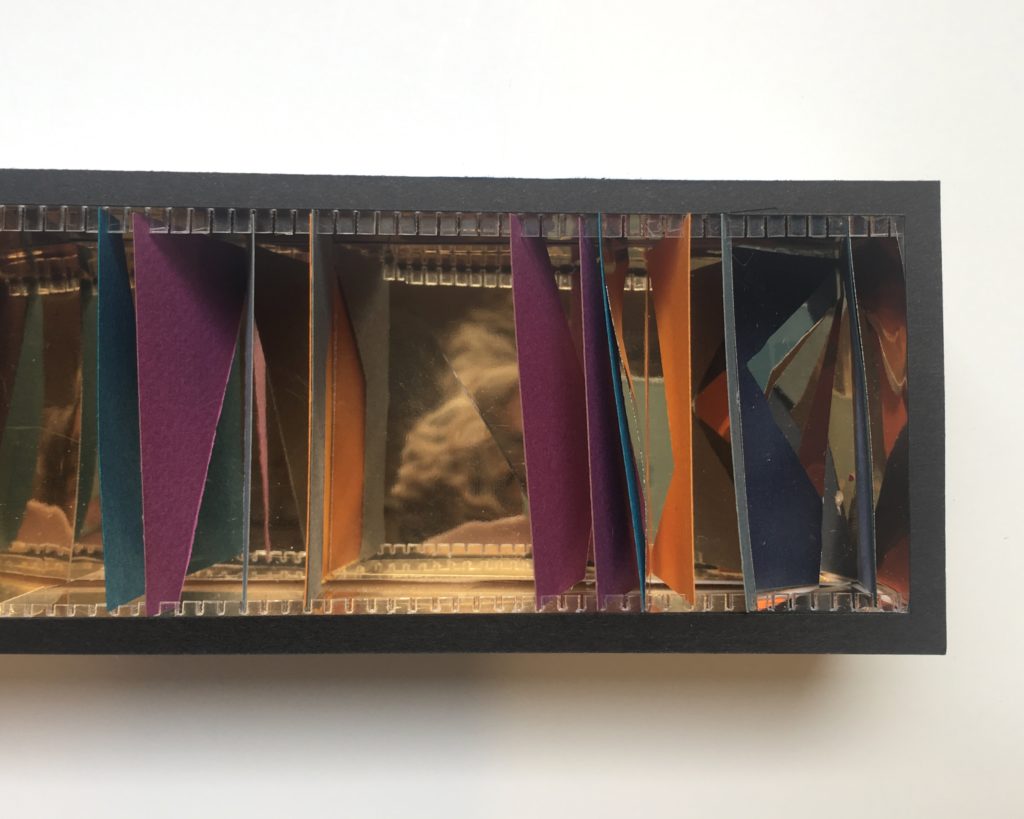

The interior space are characterized by their edges: they are evidently contained, but dimly lit and blurry. These interior spaces remain fixed and unchanging over the course of the play. In contrast, the garden begins bright and seemingly vast and wide. Yet over the course of the performance, it becomes smaller and smaller. The spaces are private — apartments of friends, the family garden, Lemon’s bedroom, a kitchen.

Time is framed through Lemon’s flashbacks, noted by the performers position on the stage. The center down-stage is present-day while flashbacks play out up-stage. While Aunt Dan is presented through flashbacks, as her monologues become more obsessive and agitated, she occupies the front of the stage closest to the audience–in line with Lemon.

The play is punctuated by periods of silence and pause among long and occasionally breathless dialogue. The words of the characters are the dominant sounds of the play. Each characters has their own tempo and accents, like a composers’ notes within a musical score. Mother’s “sound” becomes less solid, more stop-starty as the play continues. Lemon maintains a consistency – a rhythm and beat, steady without dramatic swells or falls. Yet a sweet scent permeates the air when she speaks in present day.

The play begins agitated–Lemon flashes back to her childhood in which her father is obsessed with work and her mother obsesses with Lemon’s eating. The triangle they form is tenuous and brittle. Yet when speaking of Aunt Dan and her mother, the mood shifts to light-hearted and jovial through the tales of young lovers and friends. Yet coercion and indifference to the feelings of others ripple through these retellings: an affair with a professor, Mindy’s fallback to Andy. The mood and tone shifts to become heated, contentious, arguments erupt. Yet it ends seriously, deadpan, almost without emotion in Lemon’s final monologue. The shifts in character relationships play out among the shifts in space and sound.

While most of the characters interact in groups, when Lemon flashes back to her conversations with Aunt Dan, her participation in the conversation diminishes. She becomes a shadow to Aunt Dan’s stories. Spatial note: when Aunt Dan and Lemon are in her bedroom, their shadows are prominently projected on the wall behind them. While Lemon is the central figure in communicating to the audience, she becomes increasingly overpowered by Aunt Dan’s participation. It is not until Aunt Dan is dying that Lemon claims prominence in the their relationship.

The play asks its audience to question its own relations in the world: how we each address morality, how we evaluate the morality of others, and how these individual points of view shape the world around us.

Assuming that everything is written for a reason, I can’t figure out Lemon’s juice thing. Does it indicate how indifferent she is to killing and death?

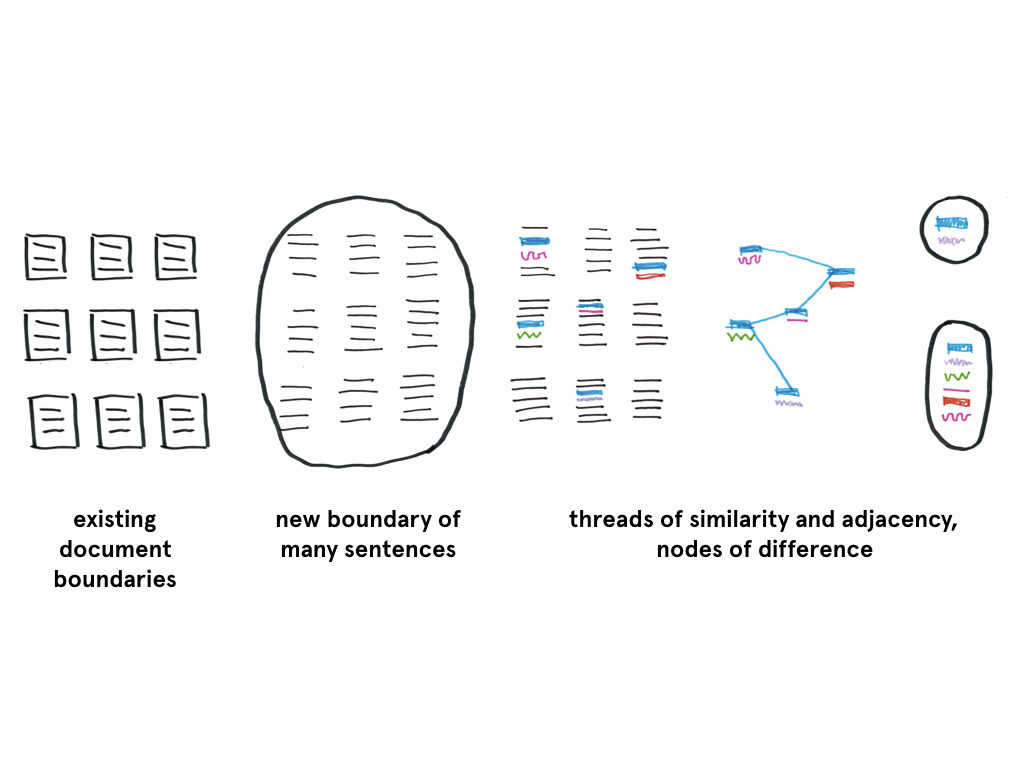

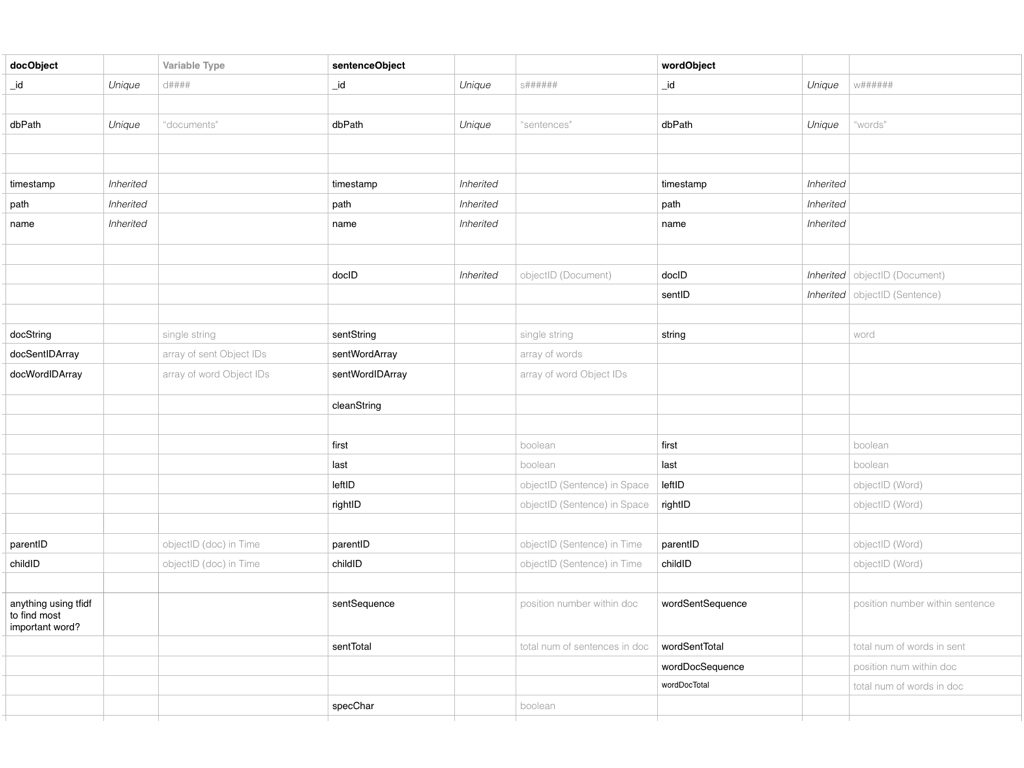

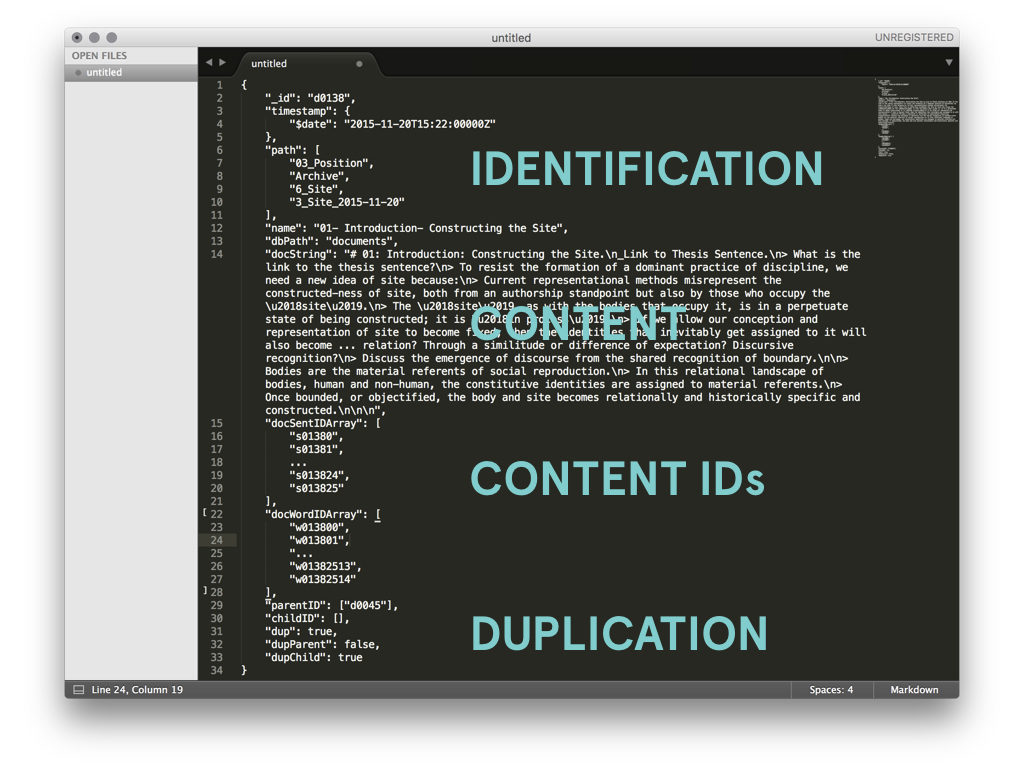

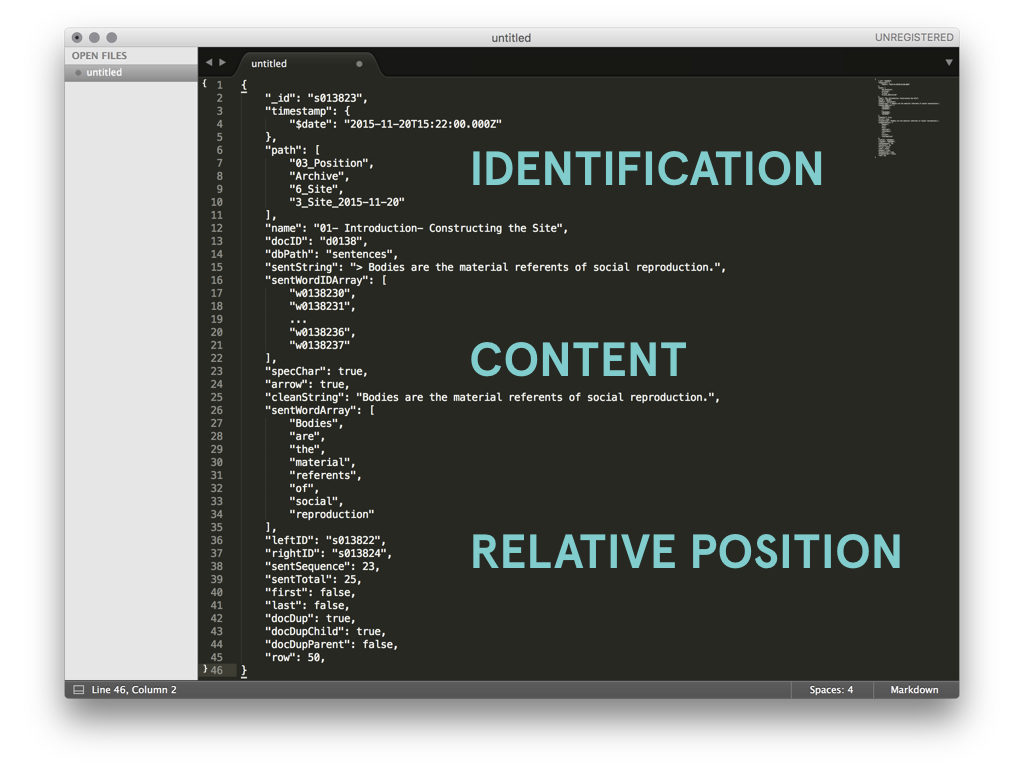

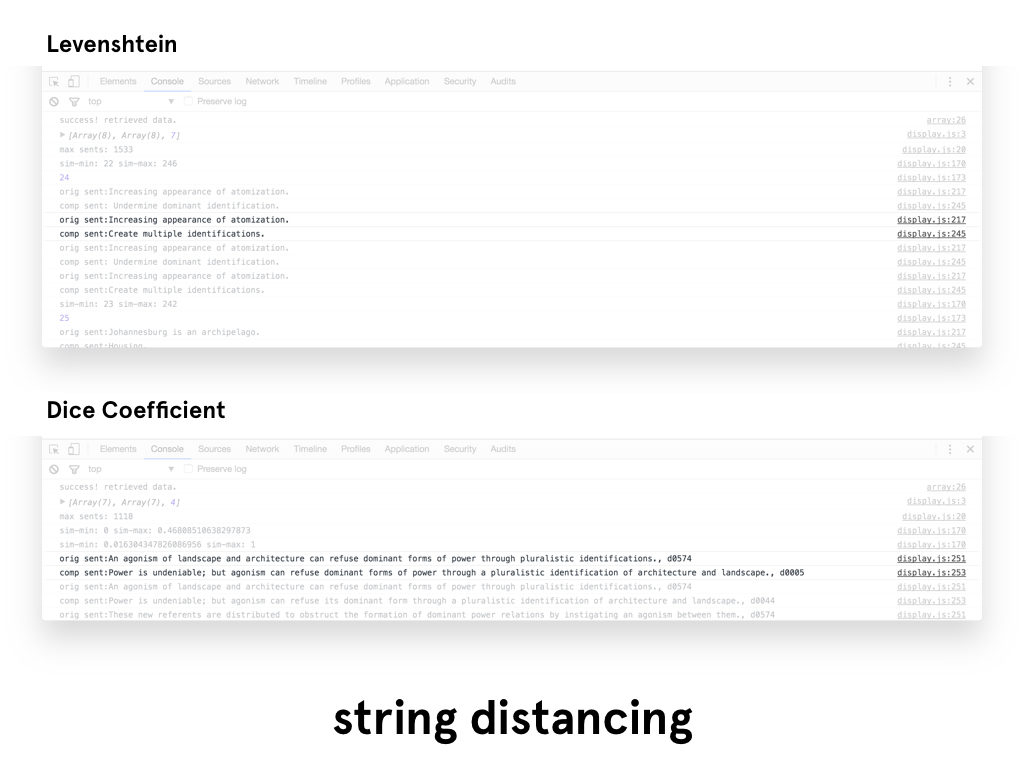

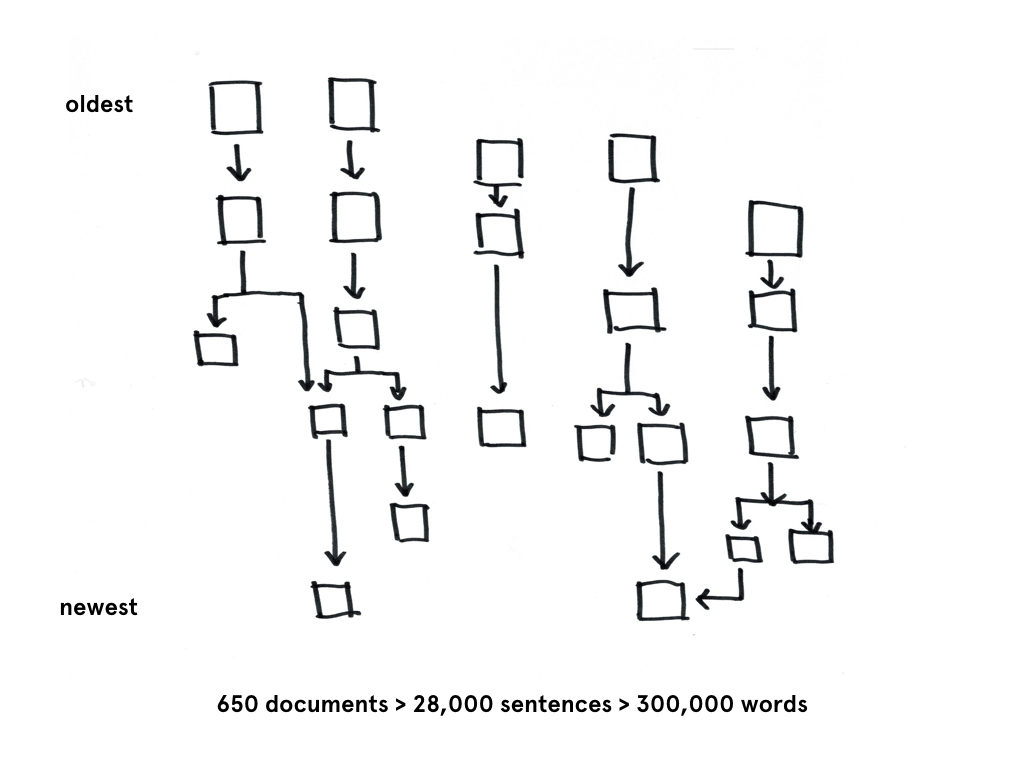

If the existing boundaries of a body of text are conventionally documents, this projects instead treats sentences as the primary object and attempts to draws new boundaries around sentences in various documents.

If the existing boundaries of a body of text are conventionally documents, this projects instead treats sentences as the primary object and attempts to draws new boundaries around sentences in various documents.