Skeleton Accumulation Studies

Documenting thoughts and works in progress

Skeleton Accumulation Studies

The structure of data has profound consequences for the design of algorithms.

– “Beyond the Mirror World: Privacy and the Representational Practices of Computing”, Philip E. Agre

To atomize the entire corpus of text, the server processes each document upload to create derivative objects: an upload object, a document object, sentence objects, and word objects. By disassociating the constituent parts of the document, they can then be analyzed and form relationships outside that original container. I’ll discuss those methods of analysis in a later blog post. The focus of this post is how the text is atomized and stored because as Agre pointed out, the organization of data fundamentally underpins the possibility of subsequent analysis.

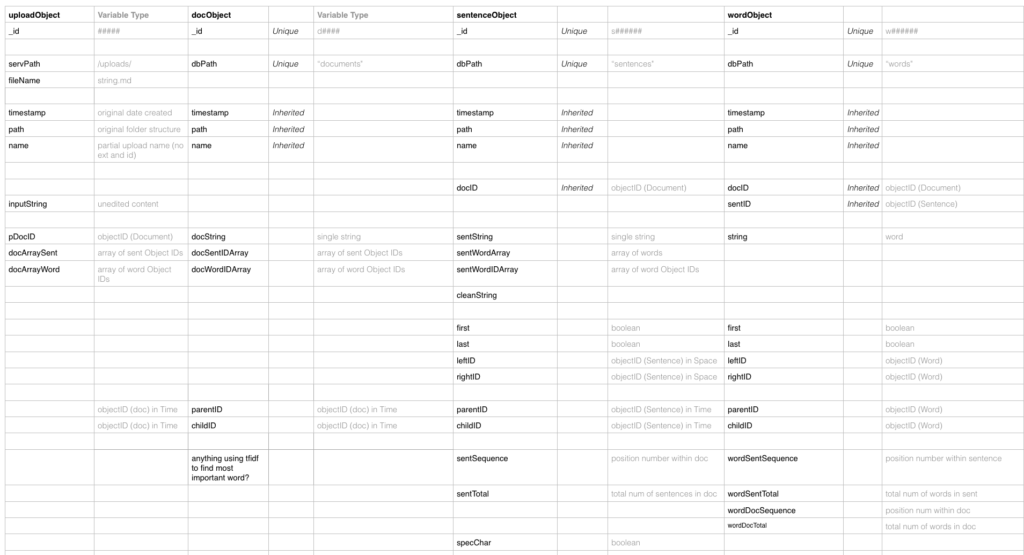

The individual objects are constructed through a series of callback functions which assign properties. These functions alternate between creating an object with its individual or inherited properties (i.e. initializing a document object with a unique ID, shared timestamp, and content string) and updating said object with the relational properties (i.e. an array of the IDs of all words contained within a document). By necessity, some of these properties can only be added once other objects are processed. The spreadsheet below shows the list of properties and how they are derived.

Additionally, as discussed in the previous post, the question of adjacency (or context) is a significant relationship. After the words or sentences are initialized with their unique IDs, the callback function then reiterates over them to add a property for the ID of the adjacent object.

At the sentence level, because the original documents were written in markdown, special characters had to be identified, stored as properties and then stripped from the string. While the “meaning” and usage of these characters is not consistent over time or across documents, they can later be used to identify and extract chunks from document.

Below is an example excerpt of a processed output, from which the individual objects are added to the database. The full code for processing the document upload can be found here.

Central Questioning

Why move the body? To control something. Thus, it is not a question of how a body should move but rather why should it move? If the answer is to contol something, what does the “controlling body” control? Either an object or environment.

Central to this question of control is a question of likeness. This is twofold: how closely does the controlled body approximate the controlling body and how closely does the physical extent of the controlling body approximate the corresponding simulated extend? Is one thing imitating another or are the markedly different? (Approximation refers to both behaviour and likeness).

The Body That Controls, Controlling the Body

The body controls as it is detected and performs standardized poses or actions. These map to the action or positioning of the controlled object or extent. This presents two realities: the reality constructed through the control of the physical body (“the simulation”) and the reality of the physical body in physical space (“the controlling”). Through engaging the simulation, our imagination places the physical body in the simulated context being controlled but presents a paradox of the controlling body still occupying itself physical context.

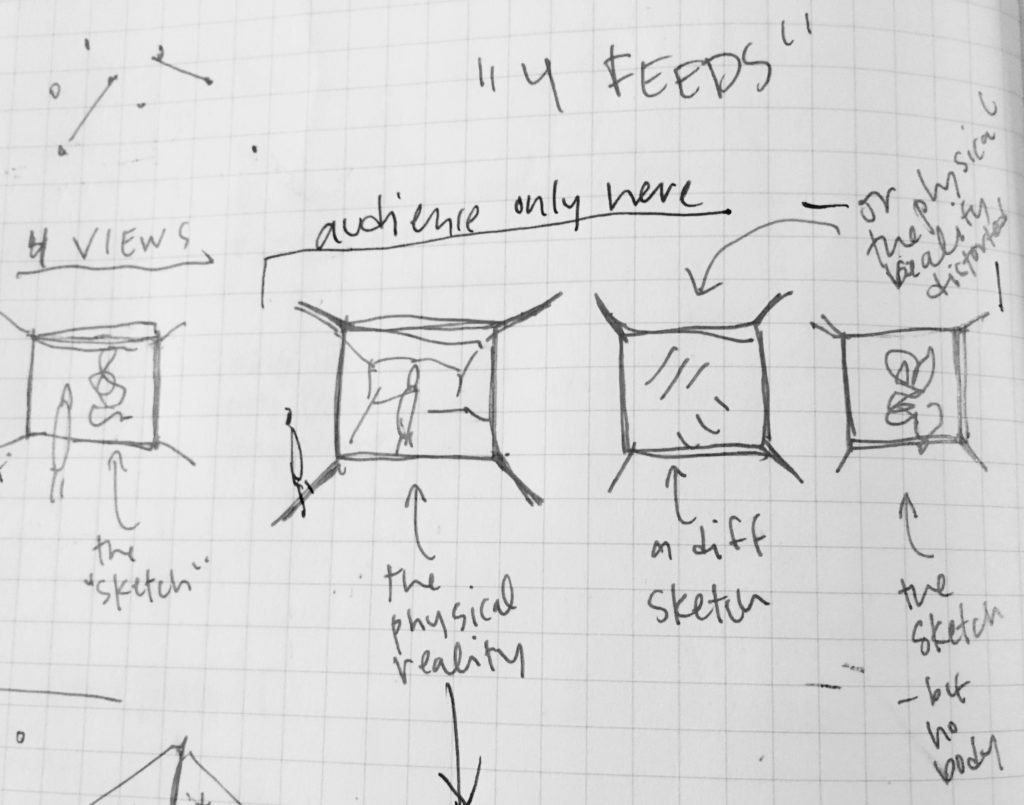

The final project proposes highlighting this paradox by displacing (and disassociating) the controlling and controlled “bodies” across different spaces. Four scenes are presented individually in four distinct and isolated spaces. In this, the performance of the controlling body is seen separately from the performance of the controlled body. When presented in isolation, the controlling body (the primary performance) is seen as both the means and ends, relying on the audience to identify the connection between.

In my initial version of ‘Many Games of Pong‘, the act of switching between controllers was so frustrating that it deterred players from doing so. This design used a 6-pin usb-to-serial adapter, which the user had to plug in “just right” before they even could play. The diagram below illustrates this initial schematic and systems.

This point of friction detracted from the key idea of players testing different controllers and de-standardizing the tools used to play games. As such, I’ve continued to develop the circuit with a focus on selecting and switching-between controllers.

The new circuit, illustrated above, uses an ESP8266 Wi-Fi chip microcontroller to eliminate wiring for sending data to the between the game and controllers. Additionally, a toggle switch, coupled with an LED, sets the state of whether or not a controller is actually connected to the game (as opposed to the hardwired connection). The server-side code keeps track of which controllers are connected and which player they’re associated with.

There’s a delay between pressing a button and seeing the effect on screen that’s still lingering, as well as the question of power. The video shows a wired connection from each controller to the computer, but that’s simply for power – not data transfer.

Code Updates

This iteration also focused on simplifying the code. My previous code for moving the paddle based on each controller was verbose and repetative. I’ve since rewritten the code to use switch cases which really simplified things.

Next Steps

The next step in the project is to create custom boards rather than use the Huzzah. Adafruit’s ESP8266 breakout board is a good reference for starting the schematic. Since some of the controllers use digital sensors (simple push buttons) while others rely on analog (photocell), the boards will be slightly different for each. Additionally, I’d like to put more time into the tangibility and tactile qualities of the sensors I use and have been hunting down various products.

Future References

When looking at a large corpus of text, containing documents that were merged, split, duplicated and edited, how can dominate tendancies and thematic pre-occupations be extracted and identified? This project asserts that these latent relationships can only be unearthed by removing the constraining ‘document boundary’ but rather looks at the text though atomizing the content into sentences.

The new relationships across the corpus are found either through the lens of ‘content’ (the words and sentences themselves and their similar counterparts), or through the lens of ‘context’ (the words and sentences around other entities).

The shape of the project is still a bit nebulous, but the images and video recording below explain the conceptual underpins of where the project is headed.